How do people know what’s true? Is technology developing too quickly for humans to adapt? Are people truly free to make their own decisions?

Over 70 community members gathered at Harwood Union High School (HUHS) on Wednesday, January 6, to contemplate these questions and more, for Socrates Café – an informal discussion based on the Socratic method of endlessly posing questions in order to stimulate critical thought.

American author Christopher Phillips began this event in 1996 and said that “for a long time, I’d had a notion that the demise of a certain type of philosophy has been to the detriment of our society. It is a type of philosophy that Socrates and other philosophers practiced in Athens in the sixth and fifth centuries B.C.” There are now over 600 cafés annually.

HUHS teacher Kathy Cadwell and students from her elective philosophy course worked together to organize the event. Cadwell asked the audience, “Wouldn’t it be exciting if school was a place where you studied things that really mattered to you?”

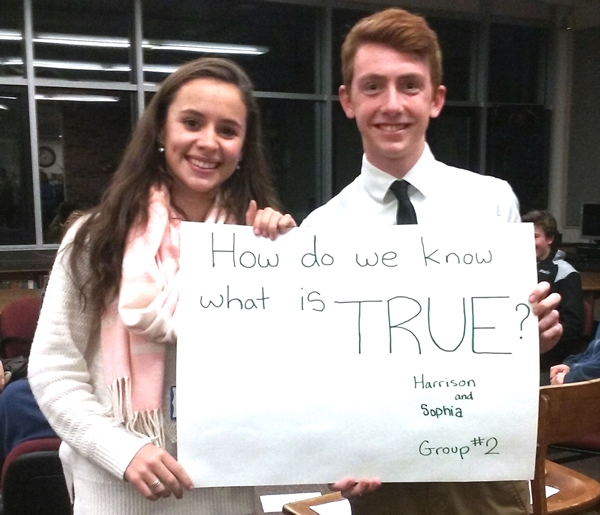

Students created six questions and facilitated discussions in groups of 15 or so and participants chose which group they wanted to attend for a 50-minute session.

Facilitators said that the group’s goal should not be to find a definitive answer but, in the spirit of Socrates, to leave with more questions. They also reminded participants that the purpose of the activity was dialogue and not debate, that there are no right and wrong answers and that silence is OK. People often perceive silence as a lack of productivity, they said – but here, it demonstrates a willingness to think through ideas carefully and that’s a good thing.

The group discussing “How do we know what’s true?” pondered whether anything beyond one’s experience is needed to evaluate truth in the world and one student asked, “What does the world look like outside of my own eyeballs?” Questions of whether morality is a kind of truth, the ease of adhering to truths that are socially sanctioned and the parallels between people’s lives and the movie The Matrix were raised.

Students, parents, teachers and community members came together in the end for a period of reflection. They said they had developed more respect for others’ opinions and valued the chance to discuss controversial ideas without those involved becoming emotionally invested. “Whenever we get into anything like this in daily life, people just seem to go further into their own ideas,” one student said.

Some students said that the dialogues have helped them socially. “It’s made me fear other people less. I didn’t feel like I was the only one to not know the answers,” one student shared, and another responded, “We’re all just really confused, which is comforting.”

Cadwell concluded to a thoroughly pleased and provoked audience, “We’re all on this big planet, spinning through space, trying to figure it all out.”