“What we’re dealing with is an opiate crisis,” said state Representative Steven Berry of Manchester. He reiterates what Vermont residents have been hearing over and over for the past years. Governor Peter Shumlin has said that that over 4,000 people were being treated for opiate addiction as of 2012, but many more remain on treatment waitlists, or far from the prospect of an antidote.

Berry sits on the House Committee on Human Services and is interested in a bill that was drafted last year which would establish a three-year clinical trial to test the effectiveness of a novel treatment for opiate dependence. The medication of interest is called Ibogaine, which has been found to significantly reduce withdrawal symptoms—the hallmark barrier to getting clean.

DETOX IS MISERY

“Detox is normally misery,” said political activist and Grand Isle resident Bonnie Scot, who brought the idea to test Ibogaine to the committee, but the time can be reduced to 36 to 48 hours with this treatment, she said. When compared to treatment that currently exists for addiction — most infamously, “maintenance drugs” like Methadone, which mimic opioids and can cause patients to form new dependencies — “it’s more of a solution,” she said.

One 10-year study conducted by University of Miami neurologist Deborah Mash found a 98 percent success rate for completely reducing withdrawal symptoms in a sample of 300 patients.

Not only has the treatment been found to reduce withdrawal symptoms in the short term, but one study found that a single treatment of Ibogaine can reduce cravings for up to six months. Researchers and patients have also said that it reduces rates of depression and increases self-awareness in patients’ psyches.

Tabernanthe iboga photo from saman.org.hu

Tabernanthe iboga photo from saman.org.hu

HOLY WOOD

Ibogaine is a psychoactive component found in the bark of a shrub called Tabernanthe iboga, native to central Africa. Its ceremonial use predates European colonization, with the first written description of it appearing in 1864 after a specimen was brought to France from Gabon. It has often been referred to as “holy wood.”

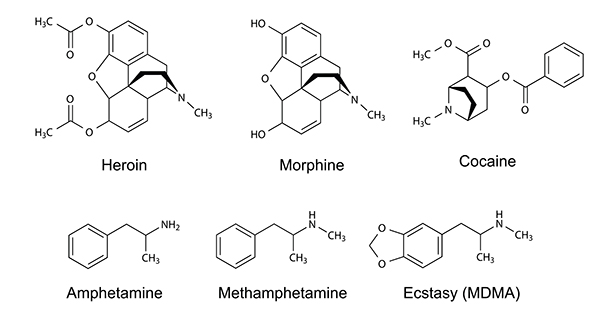

Ibogaine was isolated from the plant in 1901, and small doses were found to reduce depression in research subjects. Several studies were conducted before the chemical became criminalized shortly after Nixon declared war on drugs in 1967. It is currently a schedule 1 substance, meaning that it has a high potential for abuse and is not medically useful.

But scientific studies say otherwise, and researchers have begun to grasp its biological and chemical mechanisms, although they are complex. In a short period of time, brain neurotransmitters are radically restructured and regrown in a process that medical professionals called neurogenesis.

FIFTEEN YEARS

“It resets the brain so you feel like you have your life back,” Berry said.

Psychiatrist Martín Polanco, who has administered Ibogaine to patients for 15 years and runs a treatment center called Crossroads in Mexico where the drug is legal, said that the drug works on over 50 receptors in the brain—in short, entire systems. He calls the drug an “addiction interrupter” and said that it transforms these systems into a pre-addiction state.

Many drugs for opiate dependency, such as Methadone and Buprenorphine, mimic the effects of opioids, and “the problem is that people stay on these for a year, and it becomes even harder to get off than heroin,” Polanco explained. These are termed “agonists” by the pharmaceutical community, and “antagonists,” such as Maolxin and Narcan, are used to treat overdose. “Ibogaine is neither,” he said.

From a patient’s perspective, sharp awareness of self and one’s past can develop after taking the drug, which can last up to several days but typically several hours. This awareness is often focused on past traumas, Polanco said, which are often, studies are finding, the root of addiction.

OTHER SUBSTANCES

Whether emotional neglect, violence, sexual abuse or extreme fear, it is often early childhood trauma that forms the basis of the most severe addictions seen — not just of opioids but of alcohol and other substances as well.

“It can even be trauma that your grandparents felt, that gets transmitted, or the environment in the womb, that affects the expression of the brain,” Polanco said. “Opiates are a wonderful solution to medicate pain, at least at first, but then things get out of hand.”

Berry said that even in the state house, members are considering this connection between childhood trauma, or what they term Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE), and substance addiction. “People can be left without sense of belonging, or be unloved, misunderstood, misconnected, with no validation for their lives,” he said, “then to substitute all of these lacks, and grab onto something to fill the void.”

NOT INDIVIDUAL CHOICES

“Addictions are not individual choices in their origins,” Berry said, “but something that happens as a result of your environment.”

Scot said that the strong psychological awareness that comes with Ibogaine treatment is “one reason it was classified as schedule one.” Through visionary states, many patients describe contact with non-human, immaterial beings, “but you’re not seeing things that don’t exist,” Scot said.

Polanco explained that many patients see a fully formed 3D world that they can navigate, and “laser into aspects of your psyche that you need to work on.”

A community member based in Boston who has undergone treatment in the past said that he faced a lot “sensitive emotional stuff – regret, remorse, shame, and pain that I had been putting family through.” His addiction was seen as “an emotional burden that I suddenly became aware of, that I had been ignoring.”

CLINICAL TRIAL

What would a clinical trial for Ibogaine treatment look like? In Polanco’s clinic, staff creates a context for patients to feel safe within. Because the treatment can be a difficult journey, patients undergo rigorous medical exams and are rejected for treatment if they fail certain tests, such as cardiac tests. They also wear heart monitors during the treatment.

Berry also pointed out that some patients will not qualify because they are not willing to take the difficult journey, but one former patient said that while there is a fear component to the experience, “I’d rather face that internal kind of journey, than experience traditional detox where you’re treated like you’re a waste of space.”

“That’s the stigma surrounding addiction,” he said. “This is the most compassionate option that exists, in my opinion.”

FOLLOW UP

Many also point out that patients must also follow up treatment with therapy and a change of environment. “You’re given the insight, but you can reject it,” Scot said.

Dame said the human services committee will discuss the bill and may attach it to a larger bill that looks at Vermont’s entire system of care for opiate addiction. They will then take testimony from patients and physicians and look at scientific studies for data.

“You don’t want to say it’s a cure or a silver bullet,” Scot said, “but it’s a reset switch, and at the right dose, it stimulates your own neurons to regrow themselves and undo the damage.” This, Scot said, “is proof that this damage is reversible.”